A Woman's Path: Julie Brown, scallop diver / lobster fisherman

At this historic time when the country is on the brink of electing our first woman President, my book A Woman’s Path resonates even more today than when it was published in 1998. In profiles of 30 incredible woman who are doing interesting work, the women answer the question: How do you get to do that? I want to share these fascinating stories of women succeeding in the workplace.

Excerpt:

It took Julie five years to break into the brotherhood of lobster fishermen. Now in summer you'll find her hauling lobsters along with the men of Maine. This woman, who admits she's always liked doing something different, lives with two kitties on Vinalhaven Island, pop. 1,500. The message on her answering machine sets the tone for her current life: "You've reached the rustic but scenic boathouse of Julie Brown. Hard tellin' where I am. Probably I'm up to my butt in fish bait ... "

“My job is all about flow, ebb and flow. I live in an old boathouse. It’s about twenty by thirty feet. It’s built on posts and at high tide it’s located maybe five feet from the ocean. During a storm the ocean comes up onto my lawn.”

Vinalhaven Island is a big piece of granite in the middle of the ocean. I can hear the waves crashing and the wind blowing. And when I get caught in the grip of a northeast blow with forty-to-sixty-mile-per-hour winds, the wind blows under my house and it shakes. I rent this house and it has no running water, so I get my water from a spigot downtown. It's primitive. To take a hot shower, I heat the water on the stove and put it into a twenty-gallon plastic container. Then this boat bilge pump that's powered by a car battery pumps it through a hose with a little plastic showerhead. I try to shower every day. I smell terrible from the fish bait.

When I was a little girl I always wanted to be a pilot. I pursued that fiercely and soloed on my sixteenth birthday. I was in a program called the Civil Air Patrol. It's kind of like the junior air force. The summer I was sixteen I was chosen as the young person from Maine to go to Laughlin Air Force Base in Texas. We went through undergraduate pilot training with a class of fighter pilots. I have a picture of myself standing beside a T-38 fighter trainer. Life was wonderful. I was totally convinced that I wanted to be an Air Force fighter pilot. At the time, there weren't women fighter pilots, and I've always liked challenges. I'm very much a tomboy.

At twenty-one, I got my commercial pilot's license, but I didn't graduate from college because my grandmother had Alzheimer's and I wanted to come home to take care of her. While I was home, I was waitressing and putting out resumes. I wanted to fly Medevac, like Life Flight, where I might pick up a sick child at one hospital and fly her to a different hospital. I thought the state police would be a good place to start doing something like that. I'd just passed my physical fitness test, my written exam, and my oral boards to fly for the Maine Police Academy. It wasn't where I was going to end up, but it was a steppingstone. Then I had the accident, and that kind of shot that in the butt.

Since I'm head-injured I remember nothing about this, about flying, period. I lost all memory of anything prior to the accident. My parents have shown me pictures and I kept a diary, so I know about this, but I don't remember it.

At the time, I was waitressing at China Hill, a restaurant in the next town. I was headed to work at the restaurant. It was in January. There was a big snowstorm, a lot of slush and ice underneath the slush. The roads were extremely slippery. I was twenty-three and I was in a brand-new two-door Ford EXP, a light front-wheel-drive, cute little car. My first car I ever bought. It wasn't a year old. I started sliding, and coming down over the top of this hill was a truck loaded with cement. Because he was so heavy the road didn't feel that slippery to him, but he couldn't avoid me. I wasn't thrown from the car since I had my seat belt on; they think the sunroof, instead of popping out, popped down, and I impacted with it.

I had three stitches. That's it. I had no broken bones. I simply had massive head trauma. I was in a coma, and they wouldn't lay odds on my survival.

After a month and a half, I came out of the coma. I was tucked tightly in a fetal position and was very much like a child. Lying in bed in rehab, I overheard a neuropsychologist tell my mother that she should consider putting me in an institution. Mom said they were so happy to have me they'd gladly deal with anything because they loved me. I think deep down, even though I wasn't good at the time, that gave me an incredible amount of strength. My parents never faltered in their support. That's a debt I can never repay. A lot of families aren't close like that, and that's sad. I was also very lucky. A lot of people with extensive head injuries don't recover as completely as I have.

I had to be taught to walk and talk and do everything, tie my shoes, tell time, eat. I couldn't sit up without being tied to a chair. I could track my progress. I could say to my mother, "Momma, I feel about three today." And before long, "I feel about ten today." I went through all the stages of childhood again, right through puberty. The whole nine yards. It's amazing, the power of the brain.

After I was released from the hospital, to get out of the house and to start functioning on my own a bit, as part of my therapy I'd go lobstering with this man. He was an older man who adored me. It was like going to haul with your father. I couldn't drive, so Mom would take me down. That winter he took two divers scallop diving. I'd always loved the water, and I grew up pretty much on the water. I loved to get on that boat, a thirty-two-foot classic fiber glass lobster boat, and help with the divers. I'd run around with a towel and dry their faces.

I saw what the divers made and thought it would be wonderful to have a job where you earn that kind of money. What they make depends on the weather, visibility, how many tanks of air they dive, how they're feeling, and if they swim into a mess of scallops or not. But usually it's several hundred dollars per day. I was back at the restaurant, making in the ballpark of $6.50 an hour. I was hostessing because the manager thought it would be easier for me to seat people and not have to remember all the things on the menu and their prices.

By the end of the season, it's a six-month season, I said to the divers, "Next year I'm going to be a diver.""Oh, yeah, right," they chuckled.

Fishing in Maine is a traditional male industry. There were no women divers in my area. It's difficult to break into as a woman, especially if your father doesn't fish, or your boyfriend doesn't fish. It's hard to stand on your own two feet and jump in all alone.

I took lessons to get certified as a diver. I was in a swimming pool with my class, and the first time I took a breath off a tank with a regulator, it was a total rush. Because, you see, when you're underwater your brain is saying, Hold your breath. That's what you're always taught.

When I took that first tentative breath underwater, the air came out so sweet and so easy. I loved it immediately.

It became an all-consuming desire, a passion. And I felt better about myself under the water than I did on the surface. Underwater, you see, the fish didn't care that I was head-injured. On land, I was aware that everybody was comparing me to who I was before the accident, someone I couldn't even remember. I had people say, "Hi, Julie," and I didn't know who they were. I'd get teary and confused and scared. My mom encouraged me to say, "I've had a terrible accident. Please forgive me, but I don't remember who you are." Some people would say, "Of course you know me. Guess!" That was horrifying. I couldn't guess. I'd never seen that person before. In fact, I had, because they were my next-door neighbor.

Photo by Jill Johnson

I became a certified diver and when the season opened, I was right there. That was November 1, 1987. I'd gone to the bank and taken out a loan for $2,000. I had my own mask and snorkel and fins, and the loan paid for an Arctic dive suit, weight belt, four tanks, and my BC [buoyancy compensation] vest.

I was very, very excited and sure I was going to swim into all kinds of scallops, like I'd seen on the boat the winter before. That first day I dove three tanks of air, shallow, like thirty to forty feet, and got seven scallops all day long. I was so fascinated by the bottom that I couldn't see the scallops. I was having a wonderful time. However, seven scallops won't pay many bills.

With those seven scallops I was thinking, Oh, no, I've made a terrible mistake. But I loved diving, so I knew I had to put in the effort to be good at it. By the end of the season I was averaging forty-five to fifty pounds, bringing home $150 to $200 a day.

Now I can pretty much hold my own. I'm not the best diver, and I don't bring in the most scallops. It depends on how the scalloping is, what kind of bottom I find-meaning is it sand, is it mud, is it a big shelf, is it a rocky ledge?

It was rough getting accepted by the guys. I was called a lot of unflattering names, like bitch, the whole nine yards, the nasty stuff.

A lot of guys wouldn't have me on their boat because a woman on a boat's bad luck.

I was still diving for the old man, but if we saw someone out there we knew and pulled alongside to chat, I couldn't step on the other boat.

The other divers told me that if I was going to whine and bellyache I could stay home. I took that seriously, and once when I broke my arm, I didn't say boo. That day my mother was with me because she used to come and watch and make sure I was okay. I slipped in the boat and broke my arm in two places. Because of the head injury, I have a high tolerance for pain, and I kept diving. All I knew was, Boy, I've really given myself a good bang, and it was difficult reaching with that arm to pick the scallops up. But, you see, I didn't whine on the boat. I was afraid if I said anything they wouldn't let me come again. It wasn't until Mom and I were on our way home that I decided I ought to have my arm checked out. I was sick to my stomach, my arm hurt so bad. My car was standard and Mom couldn't drive it, so I drove to the hospital, and was that awful.

I didn't let them put a cast on because I couldn't dive with a cast. After some lengthy discussions in the E.R., they agreed to put on a plaster half-splint that I could take on and off.

I didn't go back to that boat where the guys said, "Don't whine." I went to another boat where the guy said, not thinking I'd ever dive with a broken arm, "You can get on this boat if you can put your dive suit on all alone." The wrist seals are very tight, and I had to really drive my arm in. It brought tears to my eyes but I toughed it out. Once I was in the water the pressure made the arm okay.

On a typical scalloping day I'm on the boat by six o'clock. We head out, sometimes in the dark, to where we're going to dive. The air temperature can be anywhere from in the thirties to the teens. The water temperature's probably in the low thirties. There's a barrel with hot water on the boat so we can warm our hands, or you can get into the barrel and warm your whole body. A lot of times when we're diving, ice cakes are floating on the surface around us. It's very, very cold. Without hot water on the boat I personally couldn't stand it. The dive gear covers everything but my cheeks, and they don't have much feeling. Sometimes when I come up my face is blue. But it's not so bad that I can't stand it. Weather permitting, I dive as much as I can-four to seven hours, sometimes seven days a week.

I love it down there. The serenity and the beauty. The thing I like the most is that you don't hear anything and there's this fluid motion of the plants swaying with the sea, and the colors are muted but beautiful. If you take the time to look around, it's like being a guest in another world.

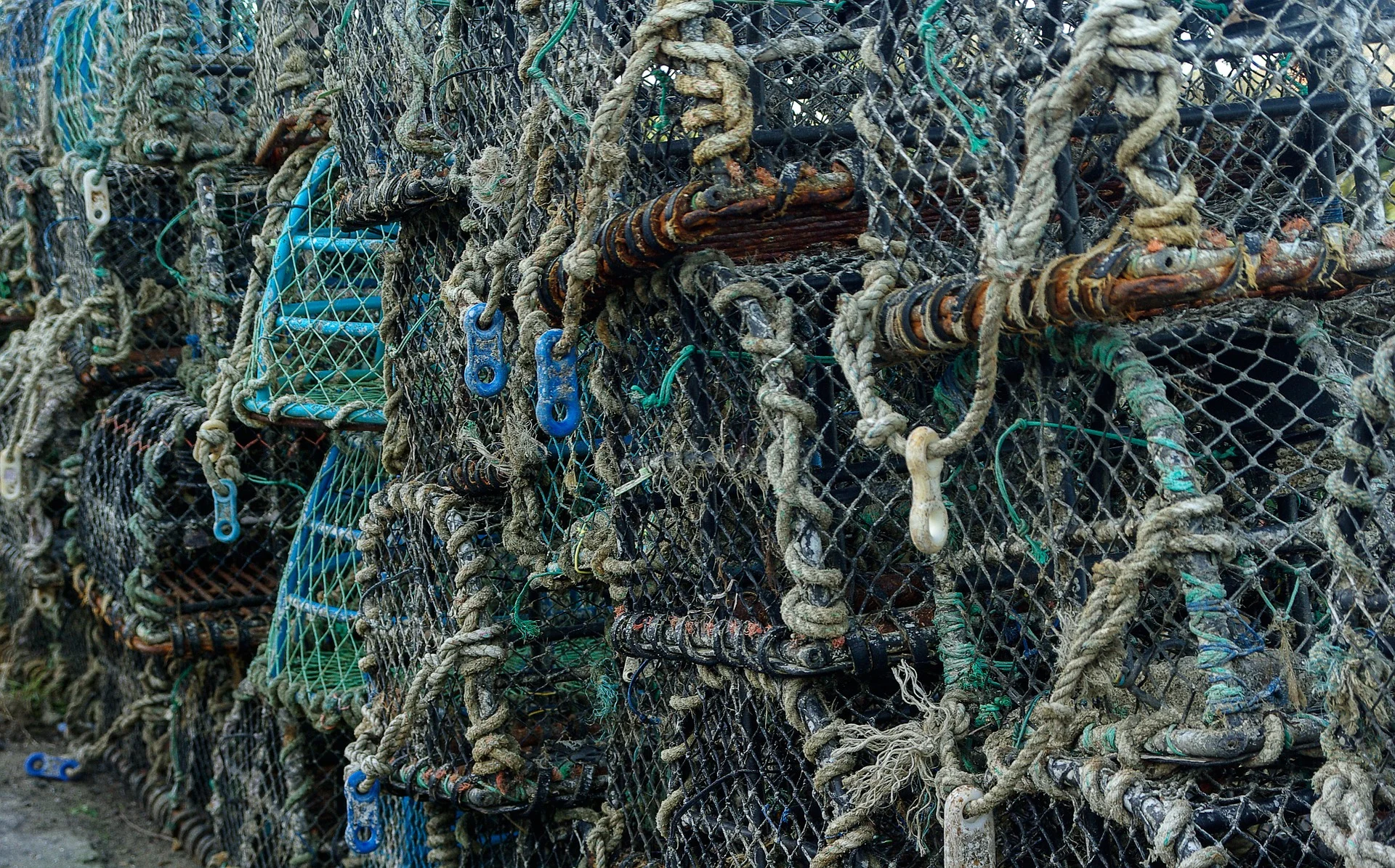

I came to Vinalhaven Island on a boat with a bunch of divers in the winter five years ago. I'd been diving and making money at it six months of the year, but the other six months I'd been working in restaurants and I hated it. All I did was talk about my diving and how I couldn't wait to get back to the ocean . I wanted to work on the water year-round. In the summer in Maine, that's lobstering. And Vinalhaven has some of the best fishermen in the state. They go at it hard, and they're serious. I came to a place where I could learn how to do this. It's very much like going to school to learn how to fish. Because it's an island and the workforce out here is smaller, their choice of who they're going to take on a boat is limited. The guys were more receptive to having a woman. I was lucky to get a stern site my first year. That means I worked the back of the boat. The captain drives the boat, picks up the buoy, puts it through what's called a pot hauler, like a winch, brings the trap aboard, and slides it down the side of the boat to the sternman. The sternman takes the lobsters out, dumps the old bait, rebaits the trap, picks out the sea urchins and trash, and slides it to the very back end of the boat. When you've picked up all the traps for an area, you start setting them back in the water. That's what a sternman does.

I'm not a lobsterwoman, a lobsterperson. I'm a lobsterman. A fisherman. A sternman. They're just words. I never got caught up in that jargon.

I started to set up something like a college syllabus for myself of things I wanted to learn that would make me a more well-rounded fisherman. I haven't gone yet, but I have a chance to go on one of the herring carriers and watch them catch the fish we use to bait the lobster traps. Right now I'm working at a lobster-buying station because I want to see that end of the business. Although I took a drastic cut in pay from what I made sterning, I can still pay my bills, and I'm learning an awful lot.

This year I' m hauling my lobster traps by hand in a twelve-foot rowboat. I have seventeen traps on seventeen separate lines. I row probably half a mile and if the wind's blowing, it's choppy. The other day I was rowing, and my little rowboat was taking water over the stern. It was rough.

But it's a way for me to gain respect. Normally, people fish where they're from. I was born in Surry, up the coast two hours from here. I have a birthright to fish the waters around Surry, but I have no birthright to fish in Vinalhaven. But here there are so many lobstermen who can teach me, where in Surry there are only four or five lobster guys, and they do it as a sideline. Here, that's what they do--they lobster. They make a whole year's pay in the spring-summer-fall. They go hard and don't have time for foolishness.

It's taken me five years to set traps here, and if I were here for the rest of my life I'd never be able to fish more than two hundred-three hundred traps. What I want is to have a thirty-six-foot brand-new lobster boat with eight hundred to a thousand traps. I can never grow to that point here. I'd have to go back to Surry.

When I get my first big boat it'll be called Grandpa's Legacy. In my family the only one who ever fished was my great-grandfather, and he fished all his life. He was a very old man when I got to know him, and we had conversations about fishing and the ocean. Somewhere deep inside I think he knew I had that love.