Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is the easiest, most friendly, delicious holiday. There's no endless shopping that results in the wrong Chanukah gift or the ugly, unwanted Christmas present. The menu is stark in its simplicity--because everyone expects turkey, and almost anyone can buy and roast a turkey, or buy a roasted turkey. Simple.

Ditch the Grief Group and Go Hiking

Medium.com

This article was first published on Medium.com April 2016.

https://medium.com/@jogiese/ditch-the-grief-group-and-go-hiking-99b120dd1244

Jo Giese, 2004, Sycamore Canyon Valley, Ventura, California

When my former husband died in 2004, a hospice counselor suggested I join her young spouses grief group. (I was flattered that, at 57, I still qualified as “young.”) One evening about a dozen grievers gathered around a conference table in an office in West Los Angeles. The large windows let in the gloom of pitch black night as we took turns telling our sad stories. An Asian man, still formally dressed in business clothes, black suit, white shirt, tie, said that after work he locked the door to his apartment, and cried. The only time he didn’t cry was when he was playing in a band, because “I can’t cry and play the sax at the same time.” Someone mentioned losing a favorite neighbor. And someone else a second cousin. Not to be too picky, but where were all the other young spouses? To me, who was new to grief, it didn’t seem like a level grieving field.

“Everyone’s grief is the worst,” said the therapist as she opened the session.

Really?

If that first group experience hadn’t been helpful, why did I try another? Because I couldn’t stop crying, and it felt like an icy cold draft was blowing in my chest, as if I’d had open heart surgery and the surgeon hadn’t closed up. The second bereavement group was at Agape, a trans-denominational spiritual center where thousands of congregants and a one-hundred-plus gospel choir met in a warehouse in an industrial area of Culver City. I persuaded a friend who had lost his wife to go with me. Tom, who was still so angry that his beautiful wife had died, had insisted once that I sit through an entire slide show of every one of their gorgeous wedding photos. During the three years he’d cared for his forty-four year-old wife as she’d battled a brain tumor, he’d let his business, designing museum exhibitions, slide; eventually, he let his staff of eighteen go; just the previous month, he’d closed his office. He mumbled about rebuilding his business — he had medical bills to pay, but stuck in grief limbo, he asked, “What for? What’s the point?”

On our way to Culver City, he said, “The question is if talking about grief in a group is healing, or leads to healing?”

“We’ll find out,” I shrugged.

We arrived early, and while Tom wandered off to the taco truck, I sat, dazed, at a picnic table that had been set up in the parking lot. A twenty-something woman wearing a pretty cotton sundress was eating a tostada salad at the far end of the table on the opposite side. She asked me what I was there for.

I hesitated. It was going to be hard enough to reveal my story inside to the grief group after it started, but opening up out here in public, in the parking lot, to a stranger? But she kept looking at me. “I’m here for the bereavement group,” I said.

“Who’d you lose?” she asked.

In the bright California Sunday sunshine, I could not believe someone was prying like this. She stared at me, waiting. Finally, and reluctantly, I revealed my loss. “My husband. We were together for seventeen years. He’s been gone for eight months.”

“I understand your loss,” she said.

Really?

“Two weeks ago my roommate’s hamster died.”

Just then Tom returned and he offered me a slice of his organic quesadilla.

“We gotta get out of here,” I whispered to him.

As I got up to leave, the woman said to me, “I hope you find your way back to joy today.”

When we were out of earshot, I told him about the hamster. “A hamster?” he said. “A hamster!”

“It wasn’t even her hamster. It was her roommate’s.”

Tom probably hadn’t laughed since Dale died four months earlier, but the hamster did the trick. It dug in and reached a raw deep place and split it wide open. “I wonder if she had a personal catharsis when she had to toss out the hamster food?” he said.

“I hear the hamster scrapbook was another trauma.” I said.

From then on my grief was pre-hamster and post-hamster. Post-hamster was when I turned the corner and realized I was probably going to be okay.

Ten years later, in 2014, when my mother, who was called Babe, died in May on Mother’s Day weekend, you can bet that I did not scout around for a bereavement group for motherless daughters, though I thought about it. Instead I laced up my boots, cinched on my fanny pack, and went hiking. With Ed.

Ed and I had been introduced via e-mail by a mutual friend. Alice wrote: What fun it would be if the two of you decided to have a meal or hike together sometime soon. Both of you have lost a spouse and both love the outdoors. So now I have made the introduction. You two take it from there. On our second date we hiked in the Santa Monica Mountains, and it was on that second date after we’d gone hiking, and we laid side by side on the double-wide turquoise chaise lounge on my deck, and after Ed had responded tremulously to my touch — I’d never felt a man tremble when I touched him — that we talked about marriage and our getting married (yes, this on our second date). Nine months later, we married on a rugged mountaintop at a nature preserve in the Santa Monica Mountains, and Babe, with her red walker — we called it her Ferrari — decorated with so many colorful flowers it looked like a moving bouquet, walked me down the dirt path which served as the “aisle.”

Babe Giese walking Jo Giese down the “aisle,” May 23, 2009

Ed had a cabin in Montana, so post-Babe that’s where we hiked. On high altitude trails with no cell reception where the trees smelled green and the air tasted fresh.

Scientists at the New York Academy of Sciences tell us that being outdoors — sometimes even looking at a picture of the outdoors — can make us smarter, can reduce stress, can be restorative, and can elevate our mood. As I velcroed a bear bell to the handle of my hiking stick, I wondered: can being in nature also make us less grief-stricken?

That summer we hiked the shady Hyalite trail to Grotto Falls with its spectacular vertical drop. If you’re extra careful you can balance on the slick stones down in the river bed, and on a hot day the powerful waterfall gives off a cool, refreshing spritz. Strolling past an alpine meadow filled with waist-high wildflowers, we hiked the strenuous (for us) Spanish Creek trail to Pioneer Falls where it scared me to death when we spotted three grizzlies just to the left of the trail. Ed had a new canister of bear spray, but still. With a guide we side-hilled on gravelly terrain up to a frightening ledge at Storm Castle, a peak we wouldn’t have been brave enough to summit by ourselves. On a top-of-the-world hike at Beehive Basin on our way up to the lake at 9,200 feet, we were forced to turn back because of a snow bank. A snow bank in July? And we slow-picnicked at Fairy Lake, a place so aptly named you wouldn’t be surprised to see gossamer fairies emerging from its pristine emerald waters. (When a friend saw my photo of Hyalite Reservoir with its perfect early morning mirror reflections, she accused me of photoshopping the picture. I told her, “You don’t need to photoshop Montana.”)

Hyalite Reservoir, Bozeman, Montana

On miles and miles of steep and rocky trails I did not think I am deliberately doing this — step after step (so many steps two toenails had already turned black) — to heal myself. I used to hike with a group in Big Sur that did a ritual before every hike. The Shinto ritual — clap-clap-bow! — is done in front of Shino temples in Japan. Before we took our first step onto a trailhead, we stopped and performed that ritual; it’s a deliberate call to attention that we were leaving civilization behind and crossing the threshold into wilderness. Without my Big Sur hiking buddies, I also did not do that prayerful ritual.

I never left for a hike without first thinking, I’d better call Mother first. After a lifetime of checking in with Mother every morning, how could it be otherwise? Out on the trail when a tear slipped down my cheek again, and I let out another long sorrowful sigh of “I miss my Mother!” it helped that Ed had known and liked Babe, too. The first time the three of us went out for dinner at a neighborhood restaurant, we had such a good time we closed the place down. When the big check eventually arrived, to our surprise we had no way to pay: Mom and I didn’t have our purses; Ed hadn’t brought his wallet. But that wasn’t the worst of it. After I signed an IOU, and promised, promised our waiter I’d return tomorrow to pay, we straggled, laughing, out to the parking lot, and that’s when the attendant asked Ed to point out his car, and he couldn’t figure out which of the four or five cars left was his.

“He can’t find his car?” laughed Babe. She’d been married to my father, the kind of handy guy who changed his own oil, and now her daughter was in love with a man who had been a fancy lawyer in Washington, D.C., but he forgets his wallet and can’t identify his car? Babe, who was 92 at the time, thought it was hilarious, and with a twinkle in her eye, never let Ed forget it.

“I can’t find it because I just bought it,” he said.

“It’s green, and we call it the Lovemobile,” I said, laughing.

That first summer post-Mom, I soothed myself in Montana’s green cathedrals. Hiking in the quiet of the woods was the balm that healed this daughter’s soul. Besides, Babe, who had loved visiting us in Montana, and who said, “Life is for the living!” wouldn’t have wanted me moping around inside in some grief group. Mother would have approved: Mother Nature as nurturer, as friend, as grief counselor.

Grotto Falls, Bozeman Montana

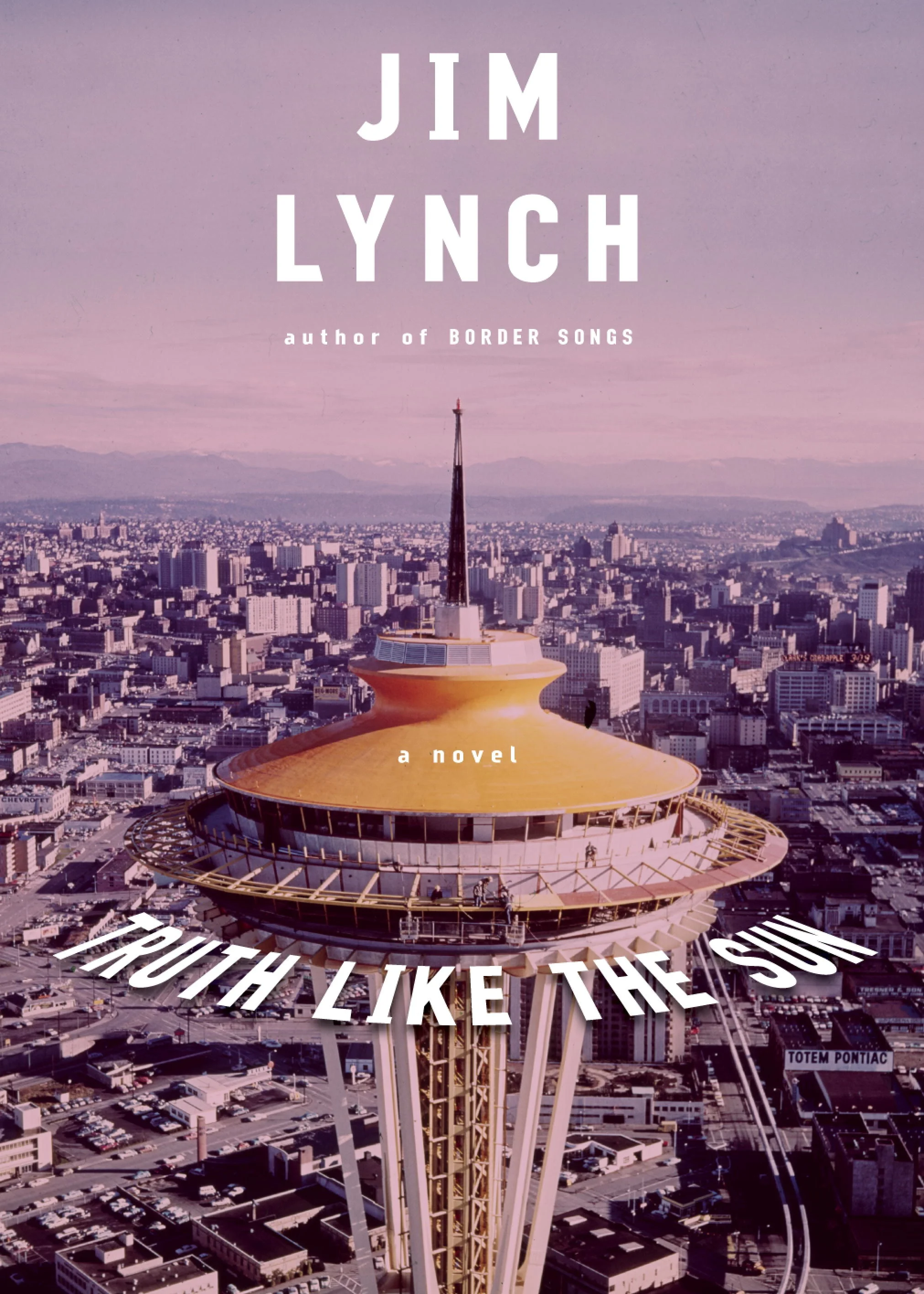

How This Journalist Renewed Her Sense Of Self While Helicopter-Hiking

Swaay.com

This article first appeared April 2017 on Swaay:

http://swaaymedia.com/journalist-renewed-sense-self-helicopter-hiking/

I’m still glowing from having just returned from helicopter-hiking.

To be dropped into a remote landscape and to hike to a hidden glacial waterfall is a heaven-on-earth experience. I’d already been heli-hiking for several days in New Zealand when I had the quintessential helicopter-hiking experience. Dion Mathewson, the pilot of the R40, the 4-passenger Robinson helicopter that he operates out of Cedar Lodge where we were staying, flew my guide and me into Boundary Creek.

He swooped us down into a wild valley in the middle of nowhere, exactly like I’d imagined. With the propeller still whirling, he yelled that he’d be back about 4:30, in six hours.

The low valley floor was crisscrossed with rocky streams, and steep mountain ranges rose on all sides. We slogged through a swampy, muddy marshland toward the trickle of a waterfall we could barely see. Since there are no predators in New Zealand, no bears and no snakes, no poison oak and no poison ivy, those weren’t the dangers we had to watch out for: Instead we had to be careful with each step–to lift your boot all the way up out of the muck, and then locate a safest spot to place it back down. This was mindful-hiking at its most extreme. Out in the middle of nowhere with no one around you don’t want to twist your ankle, or worse.

The sight of the first graceful waterfall was worth wading through swampy marshland for a hour. “Just wait,“ said Ket, my guide. “The best is yet to come.”

After inhaling that first waterfall, we headed back, and started fording the chunky creekbed. Sometimes we were wading in freezing mountain water up to our knees.

For almost four hours we crossed the creekbed sixty plus times, and still we hadn’t heard or seen this next huge waterfall. I teased Ket that it didn’t exist. Ket Hazledine, 57, and a world-class mountain climber—she intended to climb the Matterhorn in Switzerland in the summer— smiled, and kept charging, sure-footed, ahead.

Finally, we came around a corner and hidden by a mountain ridge–was the waterfall! Ket called it “Spectacular,” and it was. To reach such a stunning sight, untouched in nature, unnamed on a map, is a once-in-a-lifetime hiking experience. And it was available only because we got helicoptered into a totally inaccessible valley. At the top of the 70’ vertical drop there was no viewing ledge with a protective guard rail with the obligatory caution sign for tourists, because there were no tourists. And at the edge of the glacial pond there was also no green and yellow government sign like at other tracks in New Zealand because the “Spectacular” waterfall is off the charts.

We positioned ourselves on rocks, wearing raincoats for protection against the spray, and just when I thought things couldn’t get any better, Ket produced a picnic lunch: a salad picked fresh from her garden, and, because I’d commented that I hadn’t been getting much shellfish in New Zealand, her husband, a fish exporter, contributed crayfish. Biting into the delicious sweet crayfish, in the spray of that waterfall—and I know this will sound corny– but I felt, I’ve died and gone to heaven.

Because we’d arrived by helicopter, we didn’t have to trudge all the way back. We could lay down and relax until the helicopter came for us.

It was my best day in nature—ever, and it caused me to question why when I take out my passport I’m most likely to travel to places in nature. Whether it’s trekking in Torres del Paine National Park in Chilean Patagonia, struggling across the Nature Walk marshland in Bhutan, or hiking in the mid-Atlas Mountains in Morocco, why am I also always lacing up my hiking boots, strapping on my fanny pack, and grabbing a water bottle?

I suspect it’s because I grew up on Lake Washington in Seattle. It was around that gorgeous evergreen lake where stately evergreens grow down to its shoreline that I first started walking in nature, though I wouldn’t have put it that way when I was five years old.

Back when kids could wander out safely by themselves, I’d leave early, carefully cross Lake Washington Boulevard, meander over to the swing sets–take a pump or two–and then I’d leave the public playground and enter my very favorite private place–the walking path in the forest that led up to the middle of the peninsula. That path, always unpopulated by other people, was my hidden, secret place. I still remember the green, musty smell and the spongy softness of the footpath.

My parents and I certainly never thought little Jo Ann is getting smarter by spending her days out in nature, but recent scientific studies prove that getting outside not only does people good but makes them smarter. In an experiment at the University of Michigan, participants took memory and attention tests after strolling in a botanical garden and along city streets. The nature walk improved their results as much as 20 percent, while the sidewalk version had no effect. The research found that even looking at nature imagery had a positive effect on concentration. But we know that’s not nearly as much fun. And many of us are familiar with that well-publicized study where patients recovering from surgery were facing a brick wall versus recovering in rooms overlooking trees. The patients confronted with an expanse of brick requested narcotics at a higher rate, complained more, and spent longer in recovery than those with the leafy vista.

My next travel adventure? Hiking the glaciers in Iceland with a favorite grandson.

When you arrive home to find a bear in the house

Montana Outdoors

A different version of this article first appeared in Montana Outdoors.

Our place in Montana is called Little Bear Ranch. The name is a joke because the place isn’t really a ranch, and the bear in the kitchen wasn’t so little.

My husband, Ed, and I had gone out for a morning hike, grabbed a quick lunch, and picked up a few things at the Safeway. Coming back into the house, I’m carrying too many plastic grocery bags, and they’re just about to slip out of my arms. So, I wasn’t looking into the kitchen at the end of the hall. When I finally glance up, I am eye-to eye with a bear--a black bear, standing about eight feet away in our kitchen.

I read somewhere that a bear inside your house seems as tall as a skyscraper, and that’s about right.

Ed, who was following me into the house, says I yelled, “Bear!”

Before the kitchen, off the hallway on the right, is a laundry room, and I duck in there, dump the packages on the washer, and slide the two pocket doors close. Those flimsy doors are a screen to hide the laundry, not anything sturdy enough to keep out a bear.

Ed yells that he’s going around to the front to let the bear out. Apparently, he’d caught a glimpse of it moving away from the kitchen.

In the laundry room, I get out my cell phone to call 911, but my hands are shaking so much I can’t dial. It wouldn’t have mattered: I was so scared I’d forgotten the cell doesn’t work at the house.

Ed yells that I should come out to the garage; we’ll go get help.

How am I supposed to make a run for the garage? To escape, I have to slide apart the rickety pocket doors, but what if the bear, or bears—the previous summer we’d had three on the property--are waiting in the hall? (Last summer the bears had left paw prints on the windows, but they never ventured inside.) Even though I’m the most scared I’ve ever been, I separate the doors, and since I don’t see a bear, I run for my life to the garage.

Bear paw prints

People ask if we have guns. This is Montana. Although all the neighbors on our mountain have guns and ammo, we do not. But what difference would it have made? If we had a gun, it wouldn’t have been stored in the garage or the laundry room.

In the car Ed explains that when he got to the front door, he realized maybe opening the door, and coming face-to-face with the bear, or bears, wasn’t such a good plan.

He pulls out of the garage, and just to the left of the front door is a large picture window, and standing in the window is--the bear.

“He’s waving,” says Ed. “He’s saying, ‘Look at me! Look, who’s in charge now.’”

We head down the mountain to the fire station to get help, and I desperately dial 911. The operator connects me with Fish and Wildlife, and although they don’t have a warden in the immediate area, they can get someone to us in about 45 minutes.

At the foot of the mountain, about a mile away, volunteers are high up on ladders painting the exterior of the firehouse. Ed and I rush out, and yell up, asking if anyone has experience with bears. These are Montana macho-cowboy guys, and, of course, all three say they know about bears. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t admit it, right?

They hop into their trucks and follow us home. The volunteers throw open all the doors and search the house. No one saw the bear exit, but it’s gone. We thank them profusely.

The two wardens from Fish and Wildlife arrive ahead of schedule. “Are you armed?” is the first question they ask.

The wardens, friendly, young, attractive, and armed, walk through the house, which now stinks of a ugly musky bear smell.

“You can get rid of that nasty smell with Fabreze,” one of the wardens advises.

Bear Wardens

The wardens piece together the story. The bear entered through the window above the kitchen sink, which I’d cranked open a few inches for ventilation. The bear, it’s been determined that it was one bear, was attracted to the food on the kitchen counter: it nibbled on the small hunk of parmesan cheese, ate the 3 bagels, but left the Finnish crackers in the cellophane wrapper untouched. This bear was a dainty eater, and a graceful entry artist—he didn’t break any of the glasses in the kitchen sink.

The kitchen window is high, about shoulder-height off the deck. “Bears are acrobats,” explains the woman warden. “They can crawl up and into anything.”

In the windowseat area next to the kitchen there’s pee on the floor, and bite marks deep into the green leather upholstery. There’s bear scat in the dining room. In the living room he clawed deep angry scratches in the wooden floor. We’re told that’s a good sign: this indicates he was trying to get out, and he wasn’t a proprietary bear that wanted to stay. Trying to exit, he also tore off every screen from every window.

Bear scat

In Ed’s study, the bear bit a row of deep tooth marks in the windowsill, and that’s also where he climbed up over the electronic keyboard and stood in the window and watched us drive away to get help.

Bite marks

The wardens walk the exterior and pronounce the place, “clean.” We don’t have a outdoor barbeque, or garbage cans that are bear-attractive. Their only suggestion is that we get rid of the choke cherry bushes, which bears love.

The woman warden gives me her business card, and tells me to call her personal cell number when the bear returns.

“The bear will return?” I ask, shocked.

“Since the bear found food here, it will come back.”

They tell us the best strategy to scare the bear off is to bang pots and pans. They don’t like the noise. Pots and pans? That’s our dinky defense against a bear?

Ed, who has had this house for 14 years, is nonchalant. He never had a bear visitation inside, and he doesn’t believe the bear will return.

About a hour later, I’m in the kitchen, standing at the stove, where I have a clear view of the front door, which has glass panels on each side. The bear—our bear--is standing in the glass panel on the left, almost as if he’s about to ring the doorbell.

I yell for Ed, and while I keep the bear in sight, I call the warden, who I’m now referring to as the bear warden. To my relief, I’m not put on hold, no Muzak at a scary moment like this; she answers immediately, and says they’ll send out a trap, and remove the bear to a new territory, about 100 miles away.

A metal cylinder is hauled into our driveway, and the trap door is baited with fermentedfruit. We go to bed with every window closed and locked because we’ve learned bears can easily climb up the logs to our bedroom on the second floor.

If the bear had been trapped during the night, we figure we would have heard a ruckus--the loud clanging of the heavy trap door slamming shut. We heard nothing. The next morning I tiptoe downstairs, out to the garage where a small window looks onto the cylinder. The trapdoor is shut! Is our bear inside?

I call our bear warden, and with the warden on the phone, I cautiously approach the cylinder. The bear, looking smaller and meek and miserable, stares out at me through the bars.

Bear captured

Another warden arrives quickly to take our bear away—a adolescent bear, about two years old. (At every stage, we are totally impressed by the super-quick response of Montana’s Fish and Wildlife wardens.) This warden tells us how lucky we are. The next house he’s going to wasn’t so fortunate: In Big Sky the homeowners had gone to Bozeman for dinner, and the bear was trapped in the house for 12 hours. It rampaged the house, tore it to pieces. Luckily, we were only gone for a few hours.

Recently we remodeled our house. (Yes, we kept the windowsill with the bear bites.) A friend asked what we were going to name it. Ours is hardly one of those iconic Montana spreads with acreage, cattle, and a entrance archway that requires a name. “It deserves a name,” insisted our friend.

“Little Bear Ranch,” said Ed.

The name of our house

The following year we discover Robert McCauley, a artist who specializes in painting bears. In many of his paintings he includes a microphone because, as he says, “I want to communicate with bears. To hear what they’re saying.” A McCauley painting resides in our front entryway.

Painting by Robert McCauley

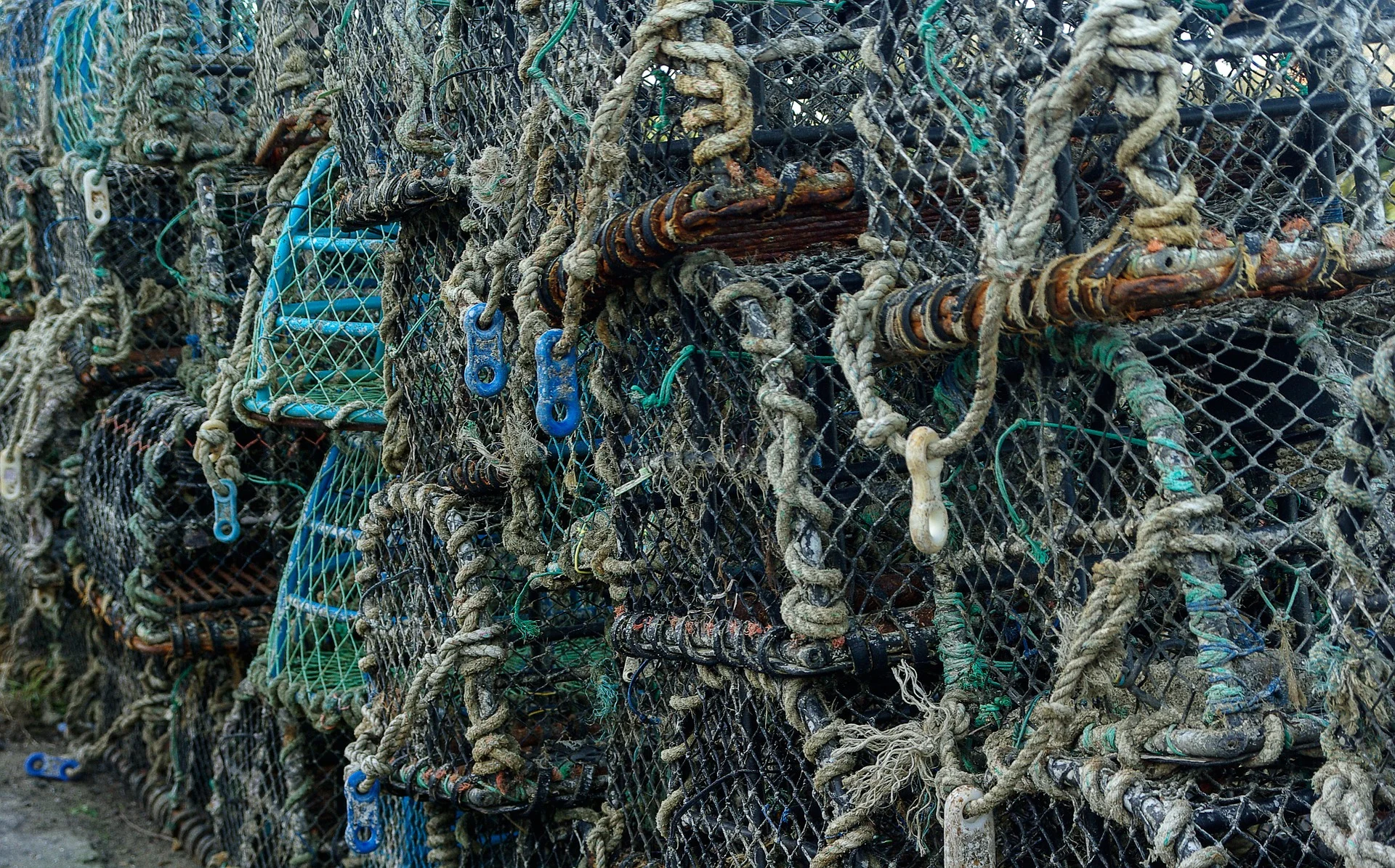

A Woman's Path: Julie Brown, scallop diver / lobster fisherman

Golden Press

At this historic time when the country is on the brink of electing our first woman President, my book A Woman’s Path resonates even more today than when it was published in 1998. In profiles of 30 incredible woman who are doing interesting work, the women answer the question: How do you get to do that? I want to share these fascinating stories of women succeeding in the workplace.

Excerpt:

It took Julie five years to break into the brotherhood of lobster fishermen. Now in summer you'll find her hauling lobsters along with the men of Maine. This woman, who admits she's always liked doing something different, lives with two kitties on Vinalhaven Island, pop. 1,500. The message on her answering machine sets the tone for her current life: "You've reached the rustic but scenic boathouse of Julie Brown. Hard tellin' where I am. Probably I'm up to my butt in fish bait ... "

“My job is all about flow, ebb and flow. I live in an old boathouse. It’s about twenty by thirty feet. It’s built on posts and at high tide it’s located maybe five feet from the ocean. During a storm the ocean comes up onto my lawn.”

Vinalhaven Island is a big piece of granite in the middle of the ocean. I can hear the waves crashing and the wind blowing. And when I get caught in the grip of a northeast blow with forty-to-sixty-mile-per-hour winds, the wind blows under my house and it shakes. I rent this house and it has no running water, so I get my water from a spigot downtown. It's primitive. To take a hot shower, I heat the water on the stove and put it into a twenty-gallon plastic container. Then this boat bilge pump that's powered by a car battery pumps it through a hose with a little plastic showerhead. I try to shower every day. I smell terrible from the fish bait.

When I was a little girl I always wanted to be a pilot. I pursued that fiercely and soloed on my sixteenth birthday. I was in a program called the Civil Air Patrol. It's kind of like the junior air force. The summer I was sixteen I was chosen as the young person from Maine to go to Laughlin Air Force Base in Texas. We went through undergraduate pilot training with a class of fighter pilots. I have a picture of myself standing beside a T-38 fighter trainer. Life was wonderful. I was totally convinced that I wanted to be an Air Force fighter pilot. At the time, there weren't women fighter pilots, and I've always liked challenges. I'm very much a tomboy.

At twenty-one, I got my commercial pilot's license, but I didn't graduate from college because my grandmother had Alzheimer's and I wanted to come home to take care of her. While I was home, I was waitressing and putting out resumes. I wanted to fly Medevac, like Life Flight, where I might pick up a sick child at one hospital and fly her to a different hospital. I thought the state police would be a good place to start doing something like that. I'd just passed my physical fitness test, my written exam, and my oral boards to fly for the Maine Police Academy. It wasn't where I was going to end up, but it was a steppingstone. Then I had the accident, and that kind of shot that in the butt.

Since I'm head-injured I remember nothing about this, about flying, period. I lost all memory of anything prior to the accident. My parents have shown me pictures and I kept a diary, so I know about this, but I don't remember it.

At the time, I was waitressing at China Hill, a restaurant in the next town. I was headed to work at the restaurant. It was in January. There was a big snowstorm, a lot of slush and ice underneath the slush. The roads were extremely slippery. I was twenty-three and I was in a brand-new two-door Ford EXP, a light front-wheel-drive, cute little car. My first car I ever bought. It wasn't a year old. I started sliding, and coming down over the top of this hill was a truck loaded with cement. Because he was so heavy the road didn't feel that slippery to him, but he couldn't avoid me. I wasn't thrown from the car since I had my seat belt on; they think the sunroof, instead of popping out, popped down, and I impacted with it.

I had three stitches. That's it. I had no broken bones. I simply had massive head trauma. I was in a coma, and they wouldn't lay odds on my survival.

After a month and a half, I came out of the coma. I was tucked tightly in a fetal position and was very much like a child. Lying in bed in rehab, I overheard a neuropsychologist tell my mother that she should consider putting me in an institution. Mom said they were so happy to have me they'd gladly deal with anything because they loved me. I think deep down, even though I wasn't good at the time, that gave me an incredible amount of strength. My parents never faltered in their support. That's a debt I can never repay. A lot of families aren't close like that, and that's sad. I was also very lucky. A lot of people with extensive head injuries don't recover as completely as I have.

I had to be taught to walk and talk and do everything, tie my shoes, tell time, eat. I couldn't sit up without being tied to a chair. I could track my progress. I could say to my mother, "Momma, I feel about three today." And before long, "I feel about ten today." I went through all the stages of childhood again, right through puberty. The whole nine yards. It's amazing, the power of the brain.

After I was released from the hospital, to get out of the house and to start functioning on my own a bit, as part of my therapy I'd go lobstering with this man. He was an older man who adored me. It was like going to haul with your father. I couldn't drive, so Mom would take me down. That winter he took two divers scallop diving. I'd always loved the water, and I grew up pretty much on the water. I loved to get on that boat, a thirty-two-foot classic fiber glass lobster boat, and help with the divers. I'd run around with a towel and dry their faces.

I saw what the divers made and thought it would be wonderful to have a job where you earn that kind of money. What they make depends on the weather, visibility, how many tanks of air they dive, how they're feeling, and if they swim into a mess of scallops or not. But usually it's several hundred dollars per day. I was back at the restaurant, making in the ballpark of $6.50 an hour. I was hostessing because the manager thought it would be easier for me to seat people and not have to remember all the things on the menu and their prices.

By the end of the season, it's a six-month season, I said to the divers, "Next year I'm going to be a diver.""Oh, yeah, right," they chuckled.

Fishing in Maine is a traditional male industry. There were no women divers in my area. It's difficult to break into as a woman, especially if your father doesn't fish, or your boyfriend doesn't fish. It's hard to stand on your own two feet and jump in all alone.

I took lessons to get certified as a diver. I was in a swimming pool with my class, and the first time I took a breath off a tank with a regulator, it was a total rush. Because, you see, when you're underwater your brain is saying, Hold your breath. That's what you're always taught.

When I took that first tentative breath underwater, the air came out so sweet and so easy. I loved it immediately.

It became an all-consuming desire, a passion. And I felt better about myself under the water than I did on the surface. Underwater, you see, the fish didn't care that I was head-injured. On land, I was aware that everybody was comparing me to who I was before the accident, someone I couldn't even remember. I had people say, "Hi, Julie," and I didn't know who they were. I'd get teary and confused and scared. My mom encouraged me to say, "I've had a terrible accident. Please forgive me, but I don't remember who you are." Some people would say, "Of course you know me. Guess!" That was horrifying. I couldn't guess. I'd never seen that person before. In fact, I had, because they were my next-door neighbor.

Photo by Jill Johnson

I became a certified diver and when the season opened, I was right there. That was November 1, 1987. I'd gone to the bank and taken out a loan for $2,000. I had my own mask and snorkel and fins, and the loan paid for an Arctic dive suit, weight belt, four tanks, and my BC [buoyancy compensation] vest.

I was very, very excited and sure I was going to swim into all kinds of scallops, like I'd seen on the boat the winter before. That first day I dove three tanks of air, shallow, like thirty to forty feet, and got seven scallops all day long. I was so fascinated by the bottom that I couldn't see the scallops. I was having a wonderful time. However, seven scallops won't pay many bills.

With those seven scallops I was thinking, Oh, no, I've made a terrible mistake. But I loved diving, so I knew I had to put in the effort to be good at it. By the end of the season I was averaging forty-five to fifty pounds, bringing home $150 to $200 a day.

Now I can pretty much hold my own. I'm not the best diver, and I don't bring in the most scallops. It depends on how the scalloping is, what kind of bottom I find-meaning is it sand, is it mud, is it a big shelf, is it a rocky ledge?

It was rough getting accepted by the guys. I was called a lot of unflattering names, like bitch, the whole nine yards, the nasty stuff.

A lot of guys wouldn't have me on their boat because a woman on a boat's bad luck.

I was still diving for the old man, but if we saw someone out there we knew and pulled alongside to chat, I couldn't step on the other boat.

The other divers told me that if I was going to whine and bellyache I could stay home. I took that seriously, and once when I broke my arm, I didn't say boo. That day my mother was with me because she used to come and watch and make sure I was okay. I slipped in the boat and broke my arm in two places. Because of the head injury, I have a high tolerance for pain, and I kept diving. All I knew was, Boy, I've really given myself a good bang, and it was difficult reaching with that arm to pick the scallops up. But, you see, I didn't whine on the boat. I was afraid if I said anything they wouldn't let me come again. It wasn't until Mom and I were on our way home that I decided I ought to have my arm checked out. I was sick to my stomach, my arm hurt so bad. My car was standard and Mom couldn't drive it, so I drove to the hospital, and was that awful.

I didn't let them put a cast on because I couldn't dive with a cast. After some lengthy discussions in the E.R., they agreed to put on a plaster half-splint that I could take on and off.

I didn't go back to that boat where the guys said, "Don't whine." I went to another boat where the guy said, not thinking I'd ever dive with a broken arm, "You can get on this boat if you can put your dive suit on all alone." The wrist seals are very tight, and I had to really drive my arm in. It brought tears to my eyes but I toughed it out. Once I was in the water the pressure made the arm okay.

On a typical scalloping day I'm on the boat by six o'clock. We head out, sometimes in the dark, to where we're going to dive. The air temperature can be anywhere from in the thirties to the teens. The water temperature's probably in the low thirties. There's a barrel with hot water on the boat so we can warm our hands, or you can get into the barrel and warm your whole body. A lot of times when we're diving, ice cakes are floating on the surface around us. It's very, very cold. Without hot water on the boat I personally couldn't stand it. The dive gear covers everything but my cheeks, and they don't have much feeling. Sometimes when I come up my face is blue. But it's not so bad that I can't stand it. Weather permitting, I dive as much as I can-four to seven hours, sometimes seven days a week.

I love it down there. The serenity and the beauty. The thing I like the most is that you don't hear anything and there's this fluid motion of the plants swaying with the sea, and the colors are muted but beautiful. If you take the time to look around, it's like being a guest in another world.

I came to Vinalhaven Island on a boat with a bunch of divers in the winter five years ago. I'd been diving and making money at it six months of the year, but the other six months I'd been working in restaurants and I hated it. All I did was talk about my diving and how I couldn't wait to get back to the ocean . I wanted to work on the water year-round. In the summer in Maine, that's lobstering. And Vinalhaven has some of the best fishermen in the state. They go at it hard, and they're serious. I came to a place where I could learn how to do this. It's very much like going to school to learn how to fish. Because it's an island and the workforce out here is smaller, their choice of who they're going to take on a boat is limited. The guys were more receptive to having a woman. I was lucky to get a stern site my first year. That means I worked the back of the boat. The captain drives the boat, picks up the buoy, puts it through what's called a pot hauler, like a winch, brings the trap aboard, and slides it down the side of the boat to the sternman. The sternman takes the lobsters out, dumps the old bait, rebaits the trap, picks out the sea urchins and trash, and slides it to the very back end of the boat. When you've picked up all the traps for an area, you start setting them back in the water. That's what a sternman does.

I'm not a lobsterwoman, a lobsterperson. I'm a lobsterman. A fisherman. A sternman. They're just words. I never got caught up in that jargon.

I started to set up something like a college syllabus for myself of things I wanted to learn that would make me a more well-rounded fisherman. I haven't gone yet, but I have a chance to go on one of the herring carriers and watch them catch the fish we use to bait the lobster traps. Right now I'm working at a lobster-buying station because I want to see that end of the business. Although I took a drastic cut in pay from what I made sterning, I can still pay my bills, and I'm learning an awful lot.

This year I' m hauling my lobster traps by hand in a twelve-foot rowboat. I have seventeen traps on seventeen separate lines. I row probably half a mile and if the wind's blowing, it's choppy. The other day I was rowing, and my little rowboat was taking water over the stern. It was rough.

But it's a way for me to gain respect. Normally, people fish where they're from. I was born in Surry, up the coast two hours from here. I have a birthright to fish the waters around Surry, but I have no birthright to fish in Vinalhaven. But here there are so many lobstermen who can teach me, where in Surry there are only four or five lobster guys, and they do it as a sideline. Here, that's what they do--they lobster. They make a whole year's pay in the spring-summer-fall. They go hard and don't have time for foolishness.

It's taken me five years to set traps here, and if I were here for the rest of my life I'd never be able to fish more than two hundred-three hundred traps. What I want is to have a thirty-six-foot brand-new lobster boat with eight hundred to a thousand traps. I can never grow to that point here. I'd have to go back to Surry.

When I get my first big boat it'll be called Grandpa's Legacy. In my family the only one who ever fished was my great-grandfather, and he fished all his life. He was a very old man when I got to know him, and we had conversations about fishing and the ocean. Somewhere deep inside I think he knew I had that love.

A Woman's Path: Deborah Doane Dempsey, Marine Bar Pilot

Golden Press

At this historic time when the country is on the brink of electing our first woman President, my book A Woman’s Path resonates even more today than when it was published in 1998. In profiles of 30 incredible woman who are doing interesting work, the women answer the question: How do you get to do that? I want to share these fascinating stories of women in the workplace-- one profile a day until Hillary is elected.

I like to make sure everyone knows the difference between a fairy tale and a sea story. A fairy tale starts, "Once upon a time ..."

A sea story starts, "This is no shit."

My mother doesn't think I should talk in that vein. But I don't hold back. I'm very direct. I get my hands dirty.

Debbie's story is of a shy, inhibited girl who grew up to become a sea captain giving orders and autographs. In the shipping industry Deborah Doane Dempsey is a legend: the first woman to graduate from a maritime academy, '76; the first American woman captain of a merchant vessel on an international voyage, '89; the first woman captain of a vessel in wartime, '90; the first woman Columbia River bar pilot, '94. On a rainy day, with the fog almost obscuring our view of the Columbia River, Debbie vacillates between laughter and tears as she tells her dramatic and difficult story.

I've always loved the water and messin' about in boats. I was raised in Essex, Connecticut, at the mouth of the Connecticut River. It's an active sailing community, a place where everybody boats. From the time I was ten and my sister, Linda, was thirteen, we'd take off for weekends-sailing a thirteen-and-a-half-foot Blue Jay and camping along the banks. Once we were headed for Martha's Vineyard on a twenty-seven-foot Tartan. There was fog, eight- to ten-foot ocean swells, and we ran off our chart. All we had left to use was a Texaco road map. And I guarantee that a road map doesn't show much of Rhode Island Sound. We pulled into Vineyard Haven after dark. That was cool! We did that!

Having to make do on the water is an incredible discipline. I have this dream of a sailing school. My school would be: load the boat up with twelve-and thirteen-year-olds and go out to sea for five days. Don't go anywhere. Just go to sea, combat the elements, and come back. You have to produce or you're not going to survive.

Photo by Jill Johnson

My dad certainly expected that one of his five kids would take over his pharmacy. Much to the disappointment of my parents I got sick of the physical sciences. After I graduated [University of Vermont] I became a bum--delivering yachts and teaching skiing. A friend of my dad's, he'd been watching me, suggested that I go up to the Maine Maritime Academy and learn what he knew I wanted to know.

Until this person, who'd graduated from Maine Maritime, made me aware that maritime schools existed, I hadn't known about them. I'd been working at the Essex Machine Works, a propeller and shaft foundry. I didn't want to work there the rest of my life, and there wasn't much security in delivering yachts. Plus, I was tired of living at my parents'. I felt the need for direction, and his suggestion was very intriguing.

There was only one woman at any of the seven maritime academies. I sent in my application to Maine Maritime, was interviewed on a Tuesday [October '73], and that Thursday they admitted me. Because I'd already graduated from college, I entered as a second-semester sophomore, so I didn't have to go through that grueling year of being a mug and the ten days of indoctrination where you're doin' tripletime up the hill in Castine.

My parents drove me to school and they didn't think I'd last two weeks because of the pseudo-military environment. You have to wear a uniform, polish your shoes, stand for inspection. The first couple of weeks were total chaos because of the publicity and the fact that the student body didn't want me there. I was forced to eat meals in the dining hall. I'd be sitting there, alone, with mashed potatoes hitting me from one side, gravy from the other, and I'd be ducking when a plate came overhead. I was spat on at morning formation. My classmates left bags of choice items outside my door. It never let up. During senior finals an ice ball with a rock in it was thrown through my dorm window.

I dealt with it by going AWOL to Commander Sawyer's residence. He taught nautical science, had a daughter about my age, and was building a cabin on the waterfront. I helped him. That was my escape.

I'd been a good student at college but at the Academy I was an excellent student because I loved what I was learning. Celestial navigation. There's nothing better than learning celestial navigation and using a sextant.

It's such a wonderful feeling to know what you want to do and to be following up on it.

It all fell into place. Castine, Maine, is a beautiful, small, seacoast port. We had this 535-foot training ship, tugboats, sailing boats. It was fantastic. I was surrounded 360 degrees by this environment -messin' about in boats-and I was doing it on that scale. A 535-foot ship. It was such a relief, and I wouldn't have to worry about my next job.

I knew what I was getting into but it's astonishing to me, even with the group I work with today, that there are males who are threatened because a woman's doing the same job a man's doing. I was a speaker at a conference on Women in Shipping. I was serving on a panel with Captain Lynn Korwatch, the first woman to sail a commercial vessel on an unlimited Master's license (she was eight months pregnant at the time), and Elizabeth Mulcahy, who runs a ship charter service out of New Jersey. A commissioner on the Board of the Maritime Pilots, probably one of two males out of a couple hundred people in the auditorium, commented to the panelists about swinging off a rope in sixty-knot winds and twenty-foot seas. He asked if we'd address the physical requirements of a woman doing a man's job. I jumped right in and said, "That's where we differ. We don't see it as women doing a man's job." I got a standing

ovation.

One of my favorite stories concerns my first job as second mate. Now you're considered the navigator of the ship. You're up there messin' with the charts, all the equipment on the bridge, laying out the courses as the Captain wants it done, using that sextant to take morning star sights and evening star sights.

I was nervous as all get out as I pulled up to the Andry Street levee in New Orleans. The Captain, who was leaning on the railing, watched me lift my seabag out of the trunk, and told one of the third mates, "Go help the cadet with her luggage." Afterward, the third mate told the Captain, "That's no cadet. That's your second mate."The Captain said, "Like hell!" He called the Lykes Shipping office and asked, "Whatcha doin' puttin' a woman on my ship?"Their response was, "Make a trip with her. You'll like her."

We sailed from Houston in pea-soup fog. I relieved the twelve-four watch after we'd already taken departure from Galveston. There are safety fairways through a horrendous number of oil rigs and I asked the third mate, "Where's the Captain? Don't you think he ought to be here in pea-soup fog? And where are we?" He said, "I think-""What do you mean, you think!" I started piecing together oil rig formations, matching them with the chart. Our vessel, the Aimee Lykes, was as long as two football fields, was on the wrong side of the fairway, and there was incoming traffic. By then Captain Dempsey was on the bridge, checking the radar, and he was not saying anything. Finally, I said, "What do you think about hauling right?"Total silence. About thirty seconds later, he said, "Yup," and hauled ninety degrees right. Later he told me he thought, No damn female's gonna tell me what to do.

Halfway through the South Atlantic on the way to Cape Town, it changed from "What's the matter now, second mate?" to "Good mornin', second mate."Two months into the sail on the east African coast, we fell in love. I called home from Mombasa, and all Mom said was, "You're not going to get married before you get home, are you?"We had a wonderful, spectacular trip. We wound up spending a week in Mtwara, Tanzania, where the original Blue Lagoon was

filmed. Jack and I were the only ones who had a good time, because there was nothing to do there while the ship discharged flour.

Jack was my role model. He didn't go to one of these fancy-dancy academies where you graduate third mate. He worked his way up by total experience and never forgot what it was like to sail mate. He taught me the confidence it takes to be a Master and a Chief Mate.

When we got back we faced quite a battle at Lykes. Jack told 'em, "You guys are right. I like her so much I' m gonna marry her."The pencil Captain Hendrix was holding snapped in two. He said, "She'll never sail Chief Mate for this outfit and you two will never sail together again, if you get married."

That was August and we got married four months later, December '78. Immediately Jack was yanked from his ship, the ship to which he'd been permanently assigned. For the next six months we fought Lykes in arbitrations and hearings in New York City. We were fighting for the ability to sail and work together on the same ship. A decision was never rendered by the arbitrator, but we won because the union [the International Organization of Masters Mates and Pilots] forced them to concede and reinstate Jack, and Vice President Hendrix was asked to retire.

Another six months later Lykes did a 180 and tried to get me on Jack's ship on a permanent basis, but I didn't have the union seniority to hold the job. I'd catch a job with him whenever I could. Our happiest times were when we were on a ship, working together. We'd solved the age-old mariner's problem of how to continue sailing and maintain a normal married life. We shared a cabin, which was no problem for anybody on the ship, and we enjoyed the foreign ports together. Izmir ... Civita Vecchia ... Singapore ... there's a lot of romance in those foreign ports.

My most dangerous assignment was the rescue of the Lyra. I was assigned Captain to the Lyra in June '89, and had made six trips in and out of the Persian Gulf crisis [Operation Desert Shield]. After the Persian Gulf War, the U.S. government bought the ship from Lykes. Lykes thought they could save some money towing it from Baltimore to New Orleans rather than recrewing it. In fifty-knot winds and twenty-foot seas the Lyra, a 634-foot vessel, eighty-nine feet wide, broke her tow off of Cape Fear [January 26, 1993]. With 387,000 gallons of fuel, no power, and no crew, the dead ship was drifting onto Frying Pan Shoals. There was no way to stop her.

I'd just gotten home to Virginia, hadn't unpacked from leaving the ship in Baltimore, and my boss asked me to fly out to the ship and attempt to anchor her.

That's another case of Jack being my mentor. He delivered me to the airport, where I was to take a helicopter to the ship. I was anxious about attempting to anchor the ship. I'd never in my life anchored a ship with two anchors. In weather like that you don't anchor-you heave to or steam back and forth. Jack was telling me what he'd do because he'd used two anchors, but he'd never been lowered by helicopter onto a dead ship--no one had. That was the very worst part-being lowered onto the deck of a ship doing thirty-five-degree snap-rolls.

Four crew members were lowered onto the deck.

“ There’s nothing blacker than a ship dead in the water in a storm at night.”

After we managed to drop the first anchor, the emergency generator failed. We had to let down the second without any power from the ship. Eight hours later the first anchor dug into the bottom. This rescue received every maritime award, and a banquet was held to honor the entire crew. Jack was there but he didn't share the podium. He considered it my show. He was a unique man.

In 1994 the Columbia River Bar Pilots recruited me. They had the state on their back to produce with affirmative action. All ports and harbors around the world have pilots who are important because they have local knowledge. A ship arrives at the Columbia River Bar, which Lloyd's of London rated as the most dangerous bar in the world. (A bar is the sand bar across the entrance to the mouth of a river where the ocean shoals up to meet it.) Without that local knowledge it's too difficult to bring in the ship, so you hire a pilot to bring you safely across the bar.

A pilot boards the ship from an eighty-seven-foot pilot boat, which runs alongside. Negotiating onto the Jacob's ladder, which can hang up to thirty feet down the side of the ship, is the most dangerous part of the job, especially since most of the work at the Columbia River Bar is done at night. Then a pilot goes up to the bridge and, since the pilot knows the depths, knows the channel, knows the bar conditions, the pilot advises the Captain what to do.

The best part about being a pilot is that you spend all your time maneuvering the ship. On a ten-day crossing of the Atlantic, you're never changing speed, doing anything, as far as ship handling. Also, with piloting, you're no longer leaving on a foreign voyage, 50 to 120 days-you're on an hour-and-a-half transit in the harbor. So, not only are you doing what you love, but every day you're home.

I could now be with Jack on a daily basis. In our eighteen years of marriage there were times when we wouldn't see each other for six months. Last summer, it was all falling into place, it was comfortable for both of us, and we bought this house. I always looked at this as our doing it together. It wasn't just me. Then Jack was diagnosed. That was awful. He died four months later of lung cancer [June 1996].

I don't have any answers right now. I' m scared of what's ahead or not ahead. What's real unattractive is coming back to this empty house. Before, whenever Jack and I weren't together, we were by ourselves, but we were never alone. Now I'm not only by myself but I'm very much alone. That's something altogether different.

I had something none of the other pilots had. I had Jack, who knew and understood every aspect of the work, and that was fun, sharing every job with someone who could advise me, support me.

After I'd been in shipping for a while, I attended an alumnae gathering at the Williams School, a day school for girls where I'd gone to high school. Everyone was listening to my sea stories, and the headmistress commented, "Deb, when you were in school here you were so shy you couldn't speak at all. Now you're nonstop!"

I told her it was because I'd found my niche, that I'm very satisfied and quite proficient at what I do. It's such a wonderful feeling to find your niche. Male or female, until you find your niche, life's difficult.

Still Wet at 90

L.A. Weekly

Goldie and author Jo Giese

Author’s Note: This is adapted from a story that originally appeared in the L.A. Weekly, and was reprinted in the Utne Reader. The L.A. Weekly editor wouldn’t use the original title –Still Wet At 90 — and insisted we change it to A Very Passionate Girl. Decades later, I’m pleased to change it back to the original, and more frisky title. The editor also asked me to change Goldie’s name. At the time Golda Mier was prime minister of Israel, and he thought readers might make an incorrect Israeli association between Goldie and Golda.

My friend Goldie was having the most erotic, passionate love affair of her life.

“Isn’t that cute!” said one man when I told him.

It was a lot of things, but “cute” it was not. Although some people couldn’t believe it, and a few were even repulsed, most smiled wistfully. “You mean there’s hope for me?”

Yes, you see, Goldie was 94.

Goldie, the artist, with one of her hooked rug masterpieces.

I’d met Goldie four years earlier, the week of her 90th birthday. A friend, who knew I was looking for an antique braided rug to go with an old quilt, said, “It’s hard to find antiques on the West Coast. But I know a woman who’s an antique who’ll make you one.”

From then on — once a month or so, as I drove the 20 freeway miles from my house in Pacific Palisades, California, to Goldie’s in Glendale — I’d wonder, Why am I, an ambitious, busy, 36-year-old, bicoastal television reporter, driving all this way to visit some old lady?

I would come to realize that my visits with Goldie had to do with eventually extracting myself from a bad first marriage, and with resolving a relationship I never got to complete with my grandmother. I understood this one day while I was buying Goldie a peignoir set for her upcoming amorous rendezvous. When I burst into tears in the lingerie department, I thought, Why am I getting so involved? If I phoned Goldie and she didn’t answer immediately, I didn’t think she was out in the garden raking leaves, or she’d driven her big black ’53 Cadillac to the grocery to get more of the vanilla ice cream she loved. My mind would race ahead: She’s gone and died on me. Just like my grandmother had.

My grandmother, Josephine, after whom I was named — Josie, Jo — was my best friend. From the time I was five years old, we shared a bedroom, a closet, a dresser, and a lifetime’s worth of feelings. My parents gave us the best bedroom — the one with the water view that looked out on Lake Washington — because they thought it was a hardship that I had to share my room. Far from it. I knew it was a special gift. Every morning as I lay in my twin bed next to hers, I’d pretend not to look as she slipped off her pink satin nightgown, and put her arms through the straps of a sturdy white corset that had a row of stiff hooks down the front. In fact, I studied her so closely that I knew every crease and line in her body. Professionally, she’d been a pastry chef, and I knew that her chocolate pudding pie, sticky cinnamon buns, and lemon meringue pie with the prettiest swirls on top, were made just for me, her roommate.

She made me pastries, and I gave her manicures. I wasn’t very steady with the clippers but it meant that I could hold her bakery-soft hands as long as I wanted.

She died when I was just 12, and 25 years later when I met Goldie, I got a chance to learn lessons my own grandmother had not lived long enough to teach me.

One afternoon Goldie and I were sitting in her kitchen with the pink café curtains, the crocheted tea cosy, and the walnut hutch that displayed plates from World Fairs. She brought out a lemon meringue pie still warm from the oven. Slicing the pie, Goldie told me about Fred, a retired railroad man who lived in a cabin on a lake in Columbus, Nebraska. Second cousins, they had met only a few months earlier at a family reunion. At 66, he was five years younger than her only son, and almost 30 years younger than Goldie.

“I wish every old lady would get herself a boyfriend. It does you a world of good!”

There was a new girlish giggle to her voice, and her white ponytail, which perched on the top of her head and fell in a corkscrew down to her shoulders, bobbed as she spoke. “The sound of his voice melts my heart. I never thought this would happen to me again.”

We helped ourselves to seconds of pie. “He’s a big man. Much bigger than Johnny [her husband who had died five years earlier].”

“How big?” I asked. I was licking sweet meringue off my fingers, and was not exactly sure to what she was referring.

“Oh, he’s at least six-foot-two.”

I pictured how large he must loom next to my diminutive four-foot-eleven friend.

“And he has such a handsome body!” As a flirtatious smile spread across her face, her powderpuff white skin turned rosy.

I dipped my tea bag in and out of a dainty, flowered china cup, and asked if she was scared about making love to a new man at her age. One might wonder about my boldness, but I was a woman of the ’80s and I wanted to know if my good friend — who was born well before the turn of the 20th century — and I are talking about the same thing. I bent closer so not to miss a word of her reply.

“No, I’m not afraid.” She spoke with the strength of a woman who had renovated houses for a living, and who still made her own ten-pound cement bricks. She had a confidence that came from knowing how. As she explained once, “It’s a blessing to know how. Sometimes I watch people staring at a broken light bulb or watching the car engine overheat or buying not enough nails at the hardware store. I watch them and laugh to myself because they don’t know how and I do!”

About Fred she said, “I’m experiencing feelings I’ve never felt before.” Her low Nebraska drawl forced me to listen closer. “ I went for years without sex before Johnny died because he lost the power of the erection. (This was pre-Viagra.) We had a good, companionable marriage and I loved him for forty years. Except it wasn’t like this terrible physical attraction Fred and I have for each other. I just want to fly into his arms.”

I drove home thinking about a fiction in our youth-oriented culture—that passion, whether sexual. intellectual, or creative, belongs only to the young. A recent dinner-table conversation came to mind where a friend, whose 14-year marriage had been monogamous, told me she wanted to have a last fling—soon. “Before I turn forty-five and it’s too late.”

Because of Goldie I knew it need never be too late. Although most of us will live longer than our parents, we are rarely encouraged to believe that life can be lived passionately to the very end.

So it was from Goldie that I learned the mysterious secrets of a passionate, creative, sensual older woman. She’d been unwelcomed child, an unwanted sister. At 40, when her first husband left her for a younger woman, she was so devastated she said that for two years couldn’t remember her name. It was her ability to overcome such hardships without ending up bitter that encouraged me. At the time I needed to leave a bad marriage. I couldn’t figure out why life was worth living one more day if I stayed married to that man, and being with Goldie, who had made it through more than 34, 310 days and still embraced each morning as a gift, gave me the inspiration I needed.

Goldie made me feel that maybe there was hope for me. If I lived long enough, maybe I’d finally get it right.

That summer Goldie decided to live with Fred for a while. I joined her in Nebraska, and drove her to the lake, and dropped her off at his small cabin. I wanted to see this scene with my own eyes: Sure enough Fred was as large as Goldie had described, he had a friendly face, and he seemed equally smitten. Goldie said she’d stay a week, or two. She stayed six.

When she returned home to California we had lunch. Because she couldn’t talk to her friends (“I’m getting accused of committing incest! Are they worried about a two-headed baby?”), or relatives (“They’re scared I’ll change my will.”), I was the only person with whom she talked about her lover. I waited until after she’d ordered her regular cottage-cheese-and-fruit salad before I asked, “So, are you still a virgin?”

She took a sip of wine. “I’m still a very passionate girl!”

Still wet at 94, I thought. Good for her. We should all be so lucky.

400 Fabulous Fridays: Celebrate Everything!

In Lessons from Babe, my quirky mother-daughter memoir, there’s a lesson “Sharing Fun Is The Whole Thing.” For Babe, sharing fun also meant “Celebrate Everything!"

In Lessons from Babe, my quirky mother-daughter memoir, there’s a lesson “Sharing Fun Is The Whole Thing.” For Babe, sharing fun also meant “Celebrate Everything!”

Babe had a friend, Eileen, a next-door neighbor, who remarried later in life. Since Eileen and her new husband had gotten such a late start, they celebrated their wedding anniversary — weekly. Why wait a year when you have fifty-two opportunities?

Since Ed and I met later in life — both of our spouses had died — and I remembered admiring Eileen’s weekly ritual, I made it ours: because we met on a Friday, and had our first date on a Friday, every Friday we celebrate our good fortune.

This Friday we celebrate 400 Fabulous Fridays.

Friends are curious and intrigued about this ritual of ours. Some ask, What do you do? Is it like a Friday night date night? Where do you go? Do you dress up?

On our 101st Friday we were in Tanzania at Faru Faru on the Grummeti River. We told our guide that it was our anniversary, and he had a special desert made for us.

But mostly how we celebrate will be disappointing for some to hear. Because usually we don’t do anything. In this super-busy, hectic, multi-tasking world of ours, what we do on Fridays is pause. First thing in the morning we take the time to acknowledge how much we mean to each other, how fortunate we are to have found each other, how lucky we are to have spent another week together. You could think of it as mindful meditation meets mindful marriage.

My Mother is Dead. This Mother’s Day, I’m Glad.

There are 85.4 million mothers in America.

On Mother’s Day this year my mother isn’t one of them, and for the first time since Babe died in 2014, I’m glad.

from left, Grandmother Josie, author Jo, mother, Babe

There are 85.4 million mothers in America.

On Mother’s Day this year my mother isn’t one of them, and for the first time since Babe died in 2014, I’m glad.

I called Mom Babe, because she asked me to — she disliked her given name, Gladys. Besides, it was fun to say, and it suited her. She was some Babe. She was so much livelier than most mothers I’ve known. Her party drugs of choice — d & d — were drinking and dancing. “Your Dad and I definitely never sat and just drank alcohol,” she said. “We danced!” ‘Never sit if you can dance’ was her mantra.

Babe and Jo

I had Babe for almost 98 years, and I was greedy for more. Until now. Because how would this mother of the 20th century, whose worst vices had been a scotch and soda at cocktail hour, and a bite of Ambien at bedtime, make sense of the fact that Tony, her first grandson, had died at 43 of an opiate addiction?

Almost daily the media repeats the C.D.C. estimate that there are 47,000 drug overdose deaths a year, primarily from addiction to prescription painkillers. Most of us can identify alcohol abuse, but who amongst us can identify the clues of opiate excess?

Tony Giese, New Years Eve, 2000

About three years ago, Tony had visited my husband and me in Southern California. Tony, who was always game for anything fun, had been hula-hooping with me and my LED lighted hoops in the backyard. It was crazy, silly fun, and I thought I was seeing the new and recovered Tony. Until the next day when I was on my way out to the grocery store, and I asked if I could pick up anything for him.

“Beer,” he said.

“Beer?” I was taken aback. I was not buying him alcohol and told him so. Years earlier, he’d entered a facility for alcohol abuse, but he checked himself out after the first week, saying the therapist said he had a personality disorder, not an alcohol problem. I was clear that I wouldn’t be an enabler with alcohol, but when and how had opiates slipped into his picture, and had I unwittingly been an enabler? Because like most people who have had the occasional surgery — a meniscus tear, a rotator cuff repair — or who have traveled to exotic places where emergency medical care is scarce, my husband and I had leftover opiates in the house (Percoset, Vicodin), and we never hid them when Tony visited. And like most Americans we weren’t used to thinking that Tony — white, college-educated, 6’3’ handsome, a talented writer, a global traveler, and a good cook — fit the stereotypical profile of a drug addict.

Tony had visited Babe the last year of her life when she was enrolled in hospice care because of her stroke. Afterward on the phone Mom had mentioned that he hadn’t looked so good; He’d gained weight, he looked pale, and bloated. But none of us connected the dots. Meanwhile, taking up the entire second shelf in her refrigerator was a white paper bag, the hospice comfort pack, an arsenal of pain pills, including hydromorphine and codeine. It did not occur to any of us that those very opiates, that in Babe’s case were on hand to numb pain at the end of life, were the “cocktail” that her talented grandson had graduated to. Why had our smart family been so dumb, so caught off-guard by this national epidemic? And what could we have done that would have been more successful than Tony’s one aborted attempt at alcohol rehab?

As my husband, Ed, and I were leaving Seattle after attending Tony’s memorial service, I said to him, “I keep thinking I have to tell Mother about this.”

Our next family trip to Seattle was supposed to have been for Tony’s wedding, not his funeral. Just that November he had proudly proposed to his fiancée with a diamond from Babe.

“What would you tell her?” Ed asked.

“I’d tell her what a heroic job my brother did at the service.”

Jim Giese, and his son, Tony Giese, New Years 2011, Montana

When my brother had phoned on January 3, his voice trembling, he said Tony was hospitalized, on life support in Bangkok, where he and his fiancée had flown for a vacation. The doctors hoped he’d pull through. Just half-an-hour later, Jim called back in tears, the only time I ever heard my 70 year-old brother cry. Tony had died.

“This is the first time I’m glad Mother isn’t alive,” I said. “So she doesn’t have to know this.”

The last time Jim saw Tony was just 17 days earlier in mid-December. Jim was home, just west of Austin, recovering from hip replacement surgery. He’d been discharged with 100 hydrocodone pills, 10 mg, for pain, as needed, the legitimate use for which this drug was intended. His surgeon had told him to keep ahead of the pain, but after taking seven pills, he quit; the bottle with the remaining 93 pills was on the kitchen counter. After paying a brief sick visit to his dad, Tony left to pick up lunch, and he had a few beers. When he returned he spotted the pills on the kitchen counter.

Jim heard the recognizable sound of the bottle of pills being opened. When he confronted his son with the half-empty bottle, Tony said, “I only took three.” He’d already swallowed them. “In case my ankle hurts.”

“Your ankle’s fine,” said Jim. “You either return all the pills you’ve stolen, or take them all if you think you need them worse than I do”.

Tony lied, saying he returned all the pills. “You want to count them?” he asked, knowing he’d kept sixteen. Then he lay on the bed next to his dad, and Jim said he could feel the stubble of his son’s beard. In a dreamy, far-away voice, Tony said, “I like pills.”

My brother knew the moment his son was conceived, and he knew then, at that moment, that his son was gone.

Tony and Jo

About halfway through Tony’s memorial service, I nudged Ed, “Is no one going to speak about the cause of his death?”

The last speaker, Jim, my brother, approached the podium slowly and reluctantly; he was using a cane because he was only seven weeks post-op. His dark suit hung limply off him; He was the one who had made the arrangements with the U.S. embassy in Bangkok to release his son’s body to Chris, his younger son who had flown to Bangkok in his stead. As Jim stood before the lectern, and looked out over the sea of hundreds of mourners in that hotel ballroom, he choked. Then my brother, always tall at 6’9,” stood even taller, as he confronted Tony’s addiction head on. Although he hadn’t been able to save his own son, he said maybe someone present today dealing with addiction in their own family, still could. For the first time in the service, I cried, and so did Ed. Babe would have cried, too.

After the family group hug where all us were shaking and sobbing, and after drinks and appetizers were passed, Marion, who I’ve known since I was 11, revealed that she had a grandson who was an addict, who had been in and out of rehab, and he’d stolen a diamond ring from her, and money. And Marion’s brother, David, who had just had a kidney transplant, said that when they have guests his wife puts their pills away because you never know.

Jo and Tony Giese, hula-hooping

The shame and stigma of friends and family of drug-addicts that have help keep this current epidemic silent. My brother’s openness in speaking about his son’s addiction, finally blew the subject wide open in our circle of friends and family.

As a grandmother, Babe would have suffered inconsolably over the loss of her grandson, and yet as a mother, she would have been extraordinarily proud of her son.

Never Sit if You Can Dance

Neither of my parents pursued any activity that today would qualify as “exercise.” Theirs was many generations before Jane Fonda’s “feel the burn!” workout videos, before isometrics and aerobics, before latex and Under Armour, before they even knew that regular exercise was good for them. My parents didn’t even know how to swim, except in a pinch Dad could dog-paddle.

But, boy, could they dance.

Young couple swing dancing in the 1940s

Neither of my parents pursued any activity that today would qualify as “exercise.” Theirs was many generations before Jane Fonda’s “feel the burn!” workout videos, before isometrics and aerobics, before latex and Under Armour, before they even knew that regular exercise was good for them. My parents didn’t even know how to swim, except in a pinch Dad could dog-paddle.

But, boy, could they dance.

Babe and Jim Giese in their courting days.

One of my favorite black and white photos from a family scrapbook was of my parents dressed up to attend a dance at the Washington Athletic Club in their courtship days. Mom, twenty-seven, was wearing a black floor-length gown that was clingy enough to show some curves, and her auburn hair was done in deep finger waves, a flirty hairstyle that was popular back then. Dad was wearing a black tuxedo. Imagine that. Dad, who ended up favoring one-piece polyester baby blue jumpsuits from Penney’s, at thirty, and courting Babe, was dressed-to-kill in a gorgeous black tuxedo. That photo captured a man and a woman who were clearly a hot couple. They looked so fresh and young, so glamorous and romantic, so pre-children. Since Babe had also told me that Dad sometimes took a room at the Washington Athletic Club, over the years I pestered her to tell me if she stayed there with him before they married. “You can tell me, Mom. It’ll just be between us.” She never said. What she did say, which was so unsatisfying, was “I think that’s private.”

Every Saturday my Mom and Dad, before they were my Mom and Dad, went to a dancehall, often the Trianon Ballroom in downtown Seattle. Babe said it was beautiful with polished hardwood floors, and it was so packed that you could hardly get in.

“We never went anywhere that didn’t have an orchestra. It was first-class all the way. You would’ve liked that place,” she said to me.

When I googled the Trianon, which is located in what is now a hipster area north of Seattle called Belltown, I learned that the dance floor had accommodated five thousand dancers. Babe said that everyone in their crowd were dancers, smooth dancers, and they danced to beautiful music, not the “junk” people listen to today.

If, as the saying goes, dancing is sex standing up, then my parents and their friends must have had a really good time gliding around those beautiful ballrooms.

Her crowd did the fox trot, swing, two-step, but nothing jumpy like the jitterbug or boogie-woogie. Babe said that sometimes the dancehall would have a Charleston Contest. “But we weren’t Charleston people,” she said.

The arrival of my brother, Jimmy, and me coincided with the passing of the big band era and the closing of the dance halls, but our parents kept dancing at home. Babe and Dad were a popular couple, and by then they had the largest house in their group, not large by current standards, but large enough by post-war 1950s middle-class standards, so the parties were always at our place. Dad had turned a daylight basement into a rec room with a highly-waxed green linoleum dance floor. That danceable space was where my brother and I skidded around in our stockinged feet, and where I cradled my new baby sister, Wendy, as I danced her to sleep. That’s also where the adults — young couples with young children, hard-working and hard-partying — danced and drank and smoked cigarettes and partied into the wee hours. That was my instructional template for being a grown up: gather a bunch of friends, some aunts and uncles, co-workers, and neighbors, roll up the rugs, and drink and dance.

Jim and Babe Giese in their later dancing days

“Your Dad and I definitely never sat and just drank alcohol,” said Babe.

“Well, so what did you do if you didn’t just sit and drink?” I asked, reverting to my best professional interview style.

“We danced!” she said, as if I were an idiot for even asking “Never sit if you can dance.”

When Herb Alpert and his trumpet blasted onto the scene with the Tijuana Brass and The Lonely Bull, Babe wore a bias-cut flared taffeta skirt, which she’d sewn herself, that swayed when she danced. By then Dad had installed a handy beer keg in the kitchen, and the adults stayed up even later.

Babe and Dad’s party drugs of choice — d & d — were drinking and dancing. Dave Barry, in writing recently about his parents drinking and partying, said “My parents and their friends probably would have lived longer if their lifestyle choices had been healthier.” Babe lived a very long and full life — until she was almost 98 — and she and her friends worked hard, partied hard, and had a lot of fun. What’s healthier than that, Dave?

I pretty much caught Babe’s sassy sense of rhythm and enthusiasm for dancing: In elementary school I raced home to dance with Dick Clark’sAmerican Bandstand on our black and white TV.

By my freshmen year at the University of Texas at the legendary Texas-OU weekend, one of the biggest rivalries in college football, I was having crazy-fun at a fraternity party. There I was, the first in my family to attend college, and I was down on all fours on a beer-soaked dance floor, “gatoring” to the Grateful Dead’s Gloria! I’m not sure that’s what Babe had in mind when she advised, Never sit if you can dance.

Being Babe’s daughter, I guess it should be no surprise that in stressful transitions I turned to dancing. After my husband died, I signed up for swing lessons at the Dr. Dance Studio in Santa Monica. But the lessons were too decorously choreographed, too contained, too formal, too much like following doctor’s orders — foot-ball-change — and in high heels. I craved something — else!